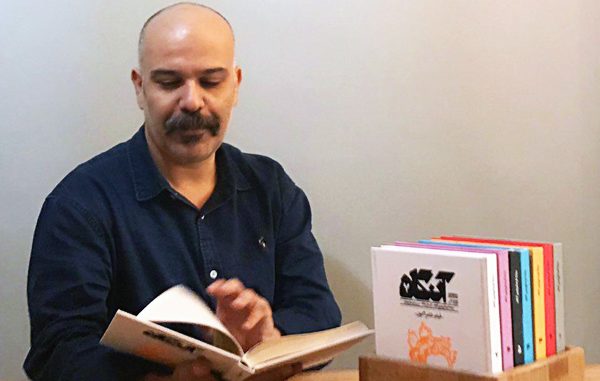

The following conversation is made between Parsagon’s editor-at-large Azadeh Ghahvie and Arash Tanhai, graphic designer and founder of Angah – an archival-conceptual magazine that documents aspects of Iranian culture and arts.

Azadeh Qahvei. Tell us about Angah.

Arash Tanhai. Angah is a bimonthly magazine with a mission located somewhere in between a book and a local community journal. It looks forward to follow the path of precedent magazines like Ketab Hafteh and Andisheh-va-Honar.

A.Q. What is Angah’s main undertaking?

A.T. To find a place in everybody’s bookshelves and library archives.

A.Q. And what would be the main challenge for that?

A.T. Well, I don’t want to bother you and myself with the story of difficulties we went through. The fact that you have Angah in your hands proves that we have done the job and the obstacles for the publication of the first issue have been overcome. In short, we live in an epoch that is not the best time for paper journals. They are suffering from and often beaten by online counterparts. And it seems to be consensus among the “sages” of our time on discouraging the “inexperienced youth” from taking the risk. But we dare to step in to prove “when there is a will, there is a way.”

A.Q. Why did you choose “café” as the subject of your first issue?

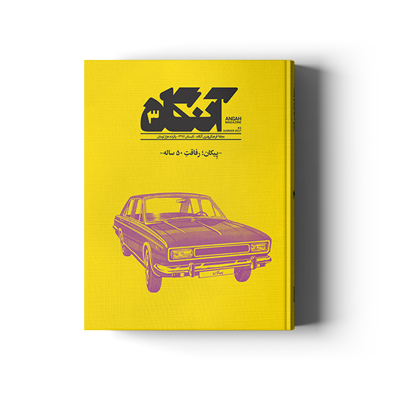

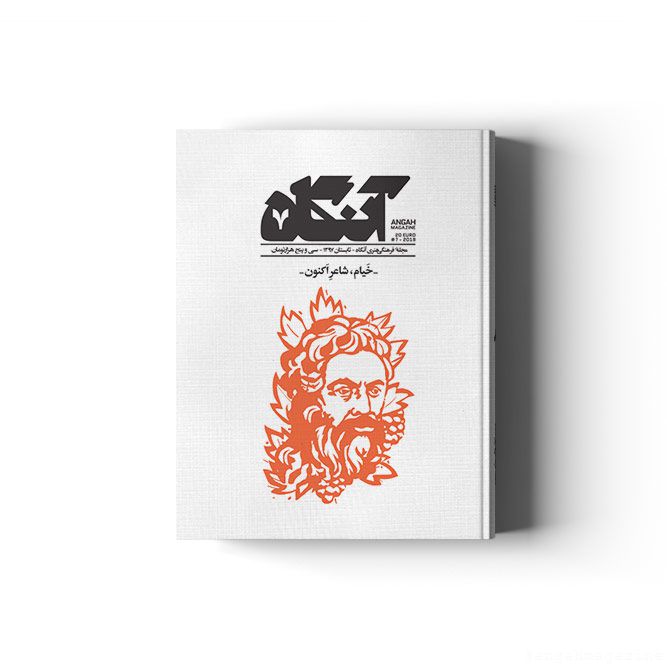

A.T. We often cover a particular subject from different angles and approaches in each issue; the first issue is dedicated to the “Café and Coffeehouse Culture” and the following issues will respectively be on Kanoon – or the Iranian Institute for Intellectual Development of Children and Adolescents, Paykan car, Lalehzar district of Tehran, and “Mount Damavand”. The subjects, though some belong to the past still continue to exist.

A.Q. What makes the cafés and coffeehouse culture attractive for your generation?

A.T. A café, a coffeehouse, or any hangout is meant to be a place for communication in the first place. Drinking a cup of coffee or tea is a good excuse to experience different levels and qualities of communication; to read a story from different vantages; to discuss and contradict, and to recount the story of the life lived there. The Polish chairs of Naderi Café, the benches of Shouka Café, the metal chairs of Nikou Sefat’s Stew Corner, the carpeted couches of Darakeh and Darband, the stone steps of the Faculty of Fine Arts, Faculty of Law, and many other places would bear witness of all the sounds and furies. Angah maintains to be the narrator of those cafés and chairs in the first issue.

A.Q. How did you start Angah?

It was one of my dreams to have a real journal, which could go beyond the school type magazines we had seen in secondary school. I used to be a big fan of Keyhan for Kids. I used to send them my paintings and writings. My first independent shopping was a Keyhan for Kids, which I did with my pocket money from a small kiosk on Hashemi Street. On other week days, I spent the money on a donut from the same place. On other weekdays, the money was often spent on donuts I got from the same kiosk.

Even later on, when I started my profession as a contributor to the magazines Tandis and Chelcheragh, I still waited for a greater occasion, because not all your ideas are incorporated into other journals no matter how high your endeavors and motivations are. Therefore, I made my decision to go and ask for a publication licence.

A.Q. And it was the first time you applied for a journal licence?

A.T. Yes, it was.

A.Q. Just one point before we move on to the next question: has Keyhan for Kids ever published any of your writings?

A.T. No, I don’t think so.

A.Q. And you kept buying it despite the fact that there was nothing published from you, or were you still hoping to see your own writings?

A.T. No, I was buying it notwithstanding the fact that they didn’t publish my stuff. In fact, they always answered my letters and that’s what I liked about them in Keyhan for Kids. They would even make recommendations. For example once I had made a drawing that was modelled after an artwork, and they responded, telling me they were more content with the previous paintings which I did on my own.

A.Q. Can we say that you were experiencing a sense of communication with this journal that was beyond what you did at school and family life?

A.T. Yes, and also when I started using the library of Iranian Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults (IDCYA) on summer of 1989, I experienced an independent way of communication with the world outside. My Mom took me there for the first time to show me the way and I would travel one kilometre every week on my own to read the books there. At that time, the drivers were kinder when they saw a kid crossing the street, compared to nowadays.

A.Q. How old were you then?

A.T. Eight years old. I had just finished my first grade at school. Couple of years ago, a friend of mine reminded me that I had taken him to the library and registered him as well, which I couldn’t remember anymore. Apparently, he was not the only one I encouraged to be a member.

A.Q. You are emphasizing the concept of independence. You also said you started Angah because you wanted to see all you expected from a journal embodied in one piece of work. Does Angah satisfy you in that sense? Do you care about what title other people would give to it?

A.T. Yes, I do for sure. Once I was asked if they should call Angah a book, or a magazine, or what. I said it is ‘Angah’ and I think it would be self-explanatory with no further explication needed. Something like BOKHARA Magazine. I was aware of the problems in the book market and those dominating the paper journal market. I wanted to bridge the gap and make the best out of both. We don’t hit records of a book selling 550 volumes in a month any more these days.

A.Q. And that is what is happening for Angah?

A.T. Yes, we ran out of all the copies for the first volume [the time of the interview]. There are a number of reasons for this. First, we decrease the final price for customers by accepting advertisement. This is the privilege of a magazine format that we benefit from in order to make the product cheaper for our audiences. A book with the same volume of paper and colours will be no less than 30 dollars (300,000 IRRs).

A.Q. And how much does Angah cost?

A.T. $15 (150,000 IRRs). Almost half of the finished price. And I am determined to keep it at this price… From the very first day I was thinking about it. I didn’t want to come up with a product that would be rejected by distributors after a year under the excuse that they don’t have enough space in their stocks. I wanted it to be kept in archives like Book of the Week which I used to buy, as a teenager, in second-hand and cheap for my archive. Nevertheless, there is still much more to do to reach that state, I am looking forward to making Angah a cultural product with no expiration date and with regular readers.

A.Q. Who are the target audiences of Angah?

A.T. There are four groups. First, art lovers, I mean all the seven arts excluding dancing which cannot find a voice in Iran; second, the art/literature students; third, those who are working in art fields, and forth, art directors in governmental and non-governmental organizations.

A.Q. So you didn’t have a general public in mind as audience?

A.T. No, we had estimated about 700,000 people as audience for our journal –

A.Q. How do you incorporate the needs of these audiences in choosing subjects for Angah?

A.T. We do the studies with our team here; you can see some of our brainstorming on the board but I am an artist and therefore very intuitive and I am the first audience of my journal. If I enjoy it, we can hope that other audiences will enjoy it, too. I told this in another interview, that if you can find five to fifteen good articles out of thirty-five or forty in a volume, you have had a reasonable purchase.

A.Q. Going back to your process of choosing the subject for each volume, to what extend are you concerned about documentation of subjects as diverse as ‘café’, ‘IIDCYA,’ etc.?

A.T. Well I have always been concerned about documentation of Iran’s contemporary history. For instance, our forthcoming issue will be on ‘Damavand’ and I can tell you that compared to the literature available on Fuji in Japan, you cannot even find one piece of work written on Damavand, unfortunately. Rather than nagging and waiting for others to take the lead, I decided to be an initiator.

A.Q. But how are you going to fill the gap between concepts? There is long way from a café in Lalehzar to Mount Damavand, the highest summit of Iran.

A.T. The answer is with different approaches that we are going to adopt. For instance, one of our volumes will be on the notion of “bridge”, and the whole concept of “transition” from a literary, sociological, or musical point of view. How the bridges have been perceived and reproduced in movies, architectural entities, photography, etc. We have editors who are experts in each field. We will start with “33 Pol,” Allahverdi Khan Bridge in Isfahan. We need to prepare ten good critical articles, ten high quality interviews, and ten work-reviews. So how we are going to approach the topics is quite clearly classified and decided: oral history, individual narrations, and the criticism on available topics.

The commonality between all these topics is that they all belong to the public sphere. For instance, we are not working on the “kitchen” but on the “alley”. There have been topics that we dropped after a while because we found them not comprehensive enough. The editorial team decided to work on those subjects which were not public enough to become books – topics such as the “Qandriz Hall” which has played an important role for visual arts.

A.Q. Please correct me if I misunderstood it. Your topics can encompass a vast area related to public life from an institution, a mountain, or a concept, to a job title, right? Your approach is documentation of the folklore with focus on art. Is that how you decide on topics?

A.T. That is right. And to answer your second question, we have a council of editors including Kaboutar Ershadi, Ali Amir-Riahi, Omid Anaraki, Marieh Shahi, Hussein Shahrabi, Behnam Sediqi, and Marzieh Vafamehr, each of which are experts in their own field and are open to comments from others. We meet every two weeks and comment on each other’s’ work as well.

A.Q. Let me demand more clarification on your approach. It is of a kind of encyclopaedic nature as it concentrates on a single topic. But one might question your approach in choosing topics: you have picked ten topics and there are twenty more which have not been touched. Is it based on your team’s decisions, and not on a survey of the audience’s needs?

A.T. Yes, our work is a cultural study and interdisciplinary in nature, and thus, detached from scientific approaches. Like a friend suggested working on football the other day, and I told him I would think about it. It is very broad but a very good field of study from sociological, literary and artistic viewpoints

A.Q. The phenomena like football have been the subject of many sociological researches, what can you offer or add to them?

A.T. We will be looking for para- (micro-) narratives of the people unlike the scientific papers or academic journals with limited number of audience. We have finished 2,000 copies in one month and our team has already considering 3,500 copies for next month and have a target of 10,000 copies of circulation very soon. Population of Iran in early 1950s was around 17 million and 40,000 copies of Ketab-e-Hafteh were sold every week in the country. Now the population is three times more and the copy of the books circulated are one third. We decided we are not going to be seen only in Tehran but in 50 other big cities based on population density. These cities can be used as hobs for smaller ones but at the moment we cannot afford distribution all through the country.

A.Q. How many cities do you cover right now?

A.T. For the first volume I cannot be sure, because all this planning started from the second issue. We know through our distributors that it is now in most of the big cities except from Zahedan, Yasuj and some other ones. But we are not happy with it right now and we are aware of the fact that how distribution is as important as the publication.

A.Q. Going back to our previous discussion, I believe most of the specialized magazines and scientific journals have lost their effectiveness in the society unlike Institute for Intellectual Development of Children and Adolescents publications which still keeps influencing a vast majority of children and people including those of low incomes.

A.T. We have also taken our targeted audience’s economic power into consideration. Like how much one meal costs for a student and whether he/she can afford $ 3.5 (15,000 Toman) to buy our bimonthly magazine and we came to the conclusion that yes it can find its place in shopping list of low income people as well.

A.Q. What do you think is the main challenge before your journal? Economic power of your audience or online journals and social media?

A.T. We wanted to increase reading per capita and also quality of reading. We have chosen 1 % of Iranian book readers as our population. They might not be necessarily those who are interested in journals and magazines, but we offer them same quality of reading materials. We are not there to increase the per capita reading but to promote per capita magazine reading.

A.Q. What are your plans to keep the aforementioned four groups of audience given the variety of the subjects you are dealing with?

A.T. The novelty is in our approach and the quality of the product we are presenting. Once I got a complement from a jewelry designer; he told me buying our magazine gives him the joy of a good purchase. Angah is hard backed and sewn binding, it means it will last at least for a good thirty years. The other example of speciality in our approach is the combination of the image with the readings. We wanted to have potent visual artists beside a strong editorial. The strength of Angah is not only in the words but in the magic of its pictures. The documentation of visual history is an important part of our plan. For example, if it is about café we will go through all the posters exhibited in Shouka café in late 1990s and 2000s. We want the reader enjoys paging over the magazine.

A.Q. How does your council choose the right people for each topic? What is the process? Is there any background studies beforehand or do you prefer to work on the topics that you already know people?

A.T. It is both. For example, for a topic like Paykan, we came across Shahin Armin’s documentary through our editor in architecture section and we were glad that someone had worked so thoroughly on the subject. On the other hand, for the Iranian Institute for Intellectual Development of Children and Adolescents, we mostly rely on the people that we knew – like Touka Neyestani.

A.Q. What was the most pleasing experience in terms of discovering a source when you were searching for a topic?

A.T. I cannot mention one, because there were many. But I enjoyed Fateh Sahbah’s article about Morteza Keyvan very much. We also try to introduce a special figure in each volume. For café, Morteza Keyvan was our focal point because he was able to bring people from different ideological spectra together in coffee shops. This article together with photos of Peyman Hooshmandzadeh who visually documented one period of Shouka, and another article about a remote café in Ilam or Tabriz have made Angah a very special collection echoing various voices. We are very sorry that we cannot be present everywhere in Iran, but we are open to anybody approaching us. Everybody can contribute to Angah by sending us a request in our web-page.

A.Q. I have no more questions, if you have any point or want to recap our discussion please go ahead.

A.T. Only one thing, I don’t know whether it is by Aydin Aghdashloo or Shamim Bahar that the “art and thought are nobody’s fief”, meaning there is no right to possessiveness and exclusion for anybody in these spheres. Angah believes in no boundary with the “other” and is open to any critique or cooperation to grow.

Leave a Reply