A graduate of the College of Fine Arts, University of Tehran, Ali-Akbar Sadeghi is one of the most prolific and successful Iranian painters and artists. His childhood infatuation with Shahnameh stories and Persian myths and legends, Sadeghi reminisces, makes an indispensable part of his worldview, “a world whose figurative representations sometimes appear in old miniature paintings or more popular forms of art, including coffeehouse painting, reverse painting on glass, imprints on wood and paper, and stunning images in lithographed books.”

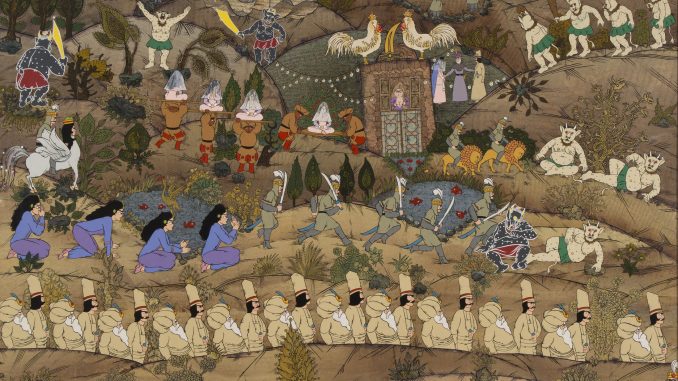

Sadeghi has been artistically active in the past 60 years. His style is a kind of Iranian surrealism, based on Iranian forms and compositions of traditional paintings, the use of Iranian iconography, and the use of Persian cultural motifs, signs, and myths, full of movement and action, in prominent and genuine oil colors, in large frames, very personal, reminiscent of epic traditional Persian paintings and illustrations, with a conspicuous mythical style. He initiated a special style in Persian painting, influenced by Coffee House painting, iconography, and traditional Iranian portrait painting, following the Qajar tradition—a mixture of a kind of surrealism, influenced by the art of stained glass.

He is among the first individuals involved in the Centre for the Intellectual Development of Children and the Youth, and was among the founders of the Film Animation department of this institute. In 1991, at the 25th anniversary of the foundation of the Institute for the Intellectual Development of Children and Young Adults, Sadeghi was honored for his outstanding achievements in book illustration and film-making, and his participation in more than 50 film and book festivals.

Aside from illustrations, he has published a number of books for the Centre for the Development of Children and the Youth, and has made seven films by using his special style in painting. Films produced by Sadeghi have won more than 20 awards at international film festivals. Also, he has won four international awards for his book illustrations.

Sadeghi’s poems were written between 2005 and 2006 during his bout of severe depression, when he was unable to pick up his brush and paint. The sense behind his poetry is to be vague and naive about the world surrounding us. The poems were born after the “Nail” series, when the artist was exhausted for painting. The “Rebirth” series is a result of the hope he gained after his poetry period. What follows are three poems translated from Persian by Farzaneh Doosti. In these writings the poet intentionally ignores punctuation and the words follow each other in a stream of consciousness style. In spite of their seemingly illogical composition, one can identify a meaningful and teleological vision of life and a narrative faithful to the patterns of fairy tales.

(1)

Why is the dagger so bloodstained? Have they beheaded Siavash, is it Siavash’s bloodstain on the vertex, like a ruby on a crown with which human beings are drawn to dungeons, and plains are sprinted over, to captivate the fish in the sea? And it’s raining still to assuage the open thirsty mouths of drain pipes, to raise the scent of clay-straw plasters of the roofs. I see the desert’s open mouth as it swallows the rain to no satisfaction, so that it can emancipate prisoners of within, so that the thorns are changed into bushes of rose of anemone and cover the plains with flowers and saturate the plains with the blood of martyrs who have been lovers once, and quench their thirst, and invade Ahriman, and bury its corpse in the ditch of darkness and conceal the tar-dark night with white snow so that the footprints of a man turning back from his journey appear on the snow, and his voice echoes in the people’s ears saying, look how exhausted I am, I’ve fallen asleep on my steed as I ride back home, I’ll throw my bow, my arrow, my spear, my dagger into the black hole, and they won’t behead any other Siavash in their eternal sepulcher, and my spear won’t hit the chest of a man whose children are awaiting him, over the hill adjacent to love, and the people will salute him and take him to a sweet sleep, and will give him his wings back: He’ll be flying to freedom.

(2)

| I will weave my carpet that I am hanging up only with colors of red and blue that bear my wrath and my love, and I will lay a kiss on the red of my flag, and every morning I will climb up the Alborz Mountain so entangled that I am in iron and steel to set the sun free from Ahriman’s gaol, and I take her through the white of dawn to shine over my green plains, and I will let rice germs flutter dance in the fields, and I will glance at the west where Ahriman is standing in the sea to drown my sun in the sea, and that is an interminable battle, and when we destroy the Ahriman of darkness the sun will be up in the sky to strew her light on us, and there won’t be any morning when a sheep’s throat is gobbled up the meat grinder, and there won’t be any morning when the death squad makes guiltless people, who’ve only stolen a piece of bread, line up before them for gunfire and coup de grace. And the heads who’d never bowed to any ruler fall off and stare at unstained soil, their crimson petals nourishing the greedy soil and the rain washing them away. And there won’t be any morning when the death squad lines up. Some time when the lights go off the electric chair short-circuits and the meat grinder stops working. It will be day forever and we will grant the Nobel Prize to Africa so that it can create a cistern as vast as the thirst of women and children so that men with callous hands can drink a fistful of water. And it will fertilize withered breasts of mothers whose starving children have swollen bellies. Once again the cattle will endow their milk to hungry people. |

(3)

The fire they have ignited for Abraham is still flaring, and Arash the Archer has not reached the summit, and Siavash is standing by the fire with his restless steed, and demons holler at valleys, and the dragon is still pining for the girl whose scent is in the air, and cavaliers are either asleep or drowse on their steeds, and I am that weary cavalier whom no one welcomes any more as they know that my sword is broken and my flag flutters no more even in the storm. I should put it for safekeeping in the safe in my house so that another cavalier could betake himself by the dry river and fight with the dragon, and the aging girl is still waiting for me. Take my steed’s saddle and tether and set him free in the plain. He is weary, too. And put my armor and helmet in the safe in my house next to the flag. I will put on a shirt made of my memories, and I will wash my face and hands with morning dew, and I will unknot my eyebrows, and I will set up a black veil at the threshold of my house, and I will write words on it that would read, the house of an old cavalier who lost his sword on his way, and the dragon is still lying at the mouth of the river, and the girl is walking toward him with a cane and white tresses. There must be a cavalier to fight with the dragon and make himself impregnable in his blood, to stop the demons’ holler, to make my voice muttering “I love you” echo in the mountains and I love you and I love you and I love you now that Arash has reached the summit, Abraham’s fire had gone out, Saivash has passed through fire to prove his innocence, tied down to the dream that keeps him awake every night till morning—in anticipation.

Image: Boasting Reproduced, Retell Collection, Film cell on canvas, 150 X 150 cm, 2015 (c) Ali-Akbar Sadeghi

Leave a Reply