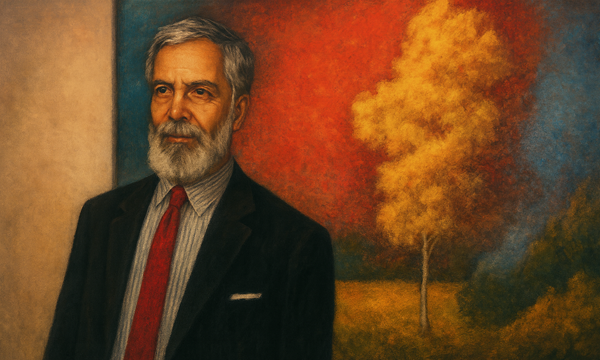

Davoud Emdadian (1944–2020) occupies a significant place in modern Iranian painting, known for landscapes that transform nature into meditations on light, solitude, and memory. Born in Tabriz, a city rich in cultural history, he pursued painting at the Faculty of Fine Arts, University of Tehran, graduating in 1969.¹ His quest for artistic growth led him to Paris, where he studied at the École des Beaux-Arts and absorbed lessons from European modernism while maintaining an Iranian sensibility.² Returning to Iran in the mid-1970s, Emdadian painted and taught, establishing himself as a leading figure of contemporary Iranian landscape art.

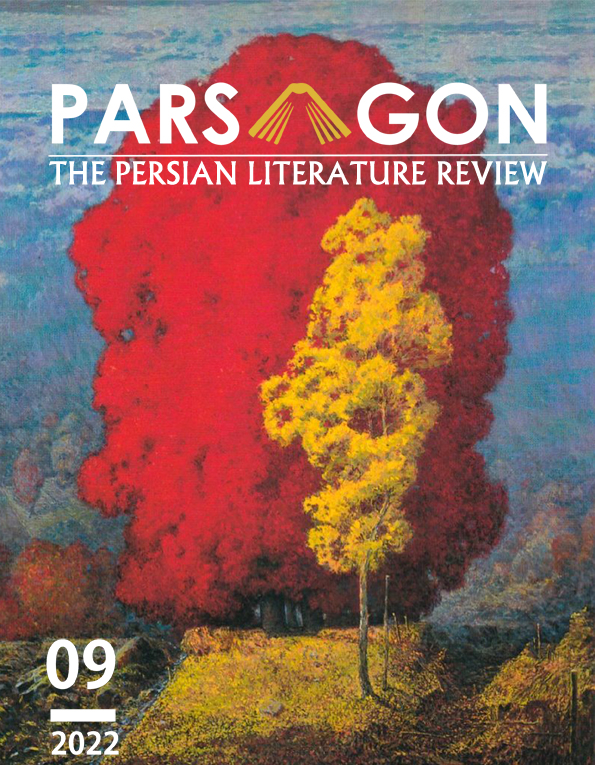

Central to Emdadian’s oeuvre is the motif of trees. These were not background details but solitary figures, monumental presences standing in dialogue with time. Rendered in muted palettes—grays, browns, soft greens—they conveyed both fragility and resilience. Critics have argued that Emdadian’s trees are existential metaphors: rooted in the earth yet reaching skyward, they articulate the tension between permanence and transience.³ In Iranian tradition, trees symbolize life, cosmic order, and spiritual renewal.⁴ Emdadian extended this lineage, transforming it into a painterly idiom of modern contemplation. His trees resonate with Persian poetry, where arboreal imagery often carries spiritual weight. In Hafez, the cypress becomes an emblem of steadfastness, while Rumi associates trees and gardens with divine presence.⁵ In the 20th century, Sohrab Sepehri—himself both poet and painter—famously wrote, “Let us not plant any trees but kindness.”⁶ Emdadian’s canvases can be read in continuity with these traditions: his trees are not only forms in nature but vessels of silence, longing, and metaphysical inquiry.

The cover of volume #09 displays a detail of an artwork by Davoud Emdadian, displaying one of his colossal trees.

Stylistically, his canvases dissolve contour into atmosphere. His restrained brushwork privileges tonal modulations over sharp definition, evoking memory and impermanence. Light plays a pivotal role: dawn and twilight dominate his visual vocabulary, those thresholds where perception falters and form softens. These liminal states mirror the human condition, poised between presence and absence. His participation in international venues, including the São Paulo Biennial in 1975, brought this vision into dialogue with global currents of landscape painting while retaining a deeply Iranian core.⁷

In an era when Iranian art was often politically explicit, Emdadian’s insistence on silence and meditative space marked a distinct stance. His trees endure not through monumentality but through stillness, inviting viewers to reflect on continuity in the face of impermanence.⁸ They remind us that the natural world can serve as a mirror for existence itself. His legacy lies in this quiet poetics: his landscapes, and above all his trees, embody the convergence of Iranian cultural memory, mystical symbolism, and modern painterly language. They stand as enduring testaments to how silence and light can become universal metaphors of being.

1. Tehran University of Fine Arts alumni records, 1969.

2. École des Beaux-Arts archives, Paris, 1970s.

3. Tavoos Quarterly Journal of Art, “Review of Emdadian’s Landscapes,” 2005.

4. Schimmel, Annemarie. Mystical Dimensions of Islam. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1975.

5. Yarshater, Ehsan (ed.). Persian Literature and Mysticism. New York: Bibliotheca Persica, 1988.

6. Sepehri, Sohrab. Hasht Ketab [Eight Books]. Tehran: Tus Press, 1977.

7. São Paulo Biennial exhibition catalogue, 1975.

8. Dabashi, Hamid. Iranian Identity and Cultural Politics. New York: Columbia University Press, 2001.

Leave a Reply