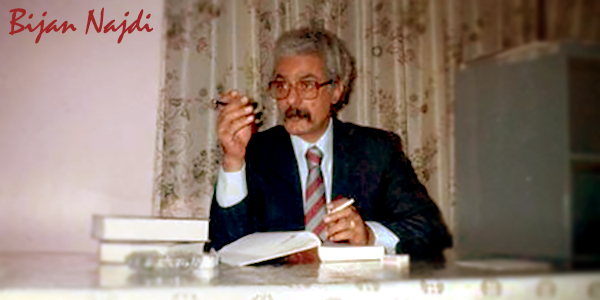

Bijan Najdi (15 November 1941 in Khash, Iran – 25 August 1997 in Lahijan, Iran) was an Iranian short story writer and poet best known for his collection The Leopards Who Have Run with Me, which was his only short story collection published during his life time. Later, his wife published a few more of his works in collections like Down the Same Streets Again, Unfinished Stories, and a more recent poetry collection titled Reality Is My Dream.

Najdi had a degree in mathematics and worked as a high school teacher in the city of Lahijan. His father was one of the communist officers who fought in the riot of Khorasan Army in August 1945 and was subsequently killed by a number of guards while escaping the military base. In 1970, he married Parvaneh Mohseni Azad with whom he had two children. Bijan Najdi died of lung cancer at the age of 56 on 25 August 1997 in Lahijan.

Najdi flickered only for a very short period in the sky of Iranian fiction writing. While he lived no more than 56 years, he started his literary career only three years prior to his death. Despite his short-time career, he was awarded many literary prizes in Iran including the Gardoon Literary Award in 1995. In 2000, his posthumous work, Down the Same Streets Again was the elected work by Journalists and Press Critics. He also won the Farapooyan Poetry Award and a few other prizes for both his prose and poetry. Najdi wrote poems both in his mother tongue, Gilaki, and Persian. A few of his short stories were also adopted after his death for short films.

Najdi is considered as one of the pioneer Iranian postmodern writers whose writings flows between realism, surrealism and magic realism. His prose is characterized by a rich metaphorical language, innovative similes, personifications, poetic exaggerations, stream of consciousness, and a nonlinear narrative style. The narrators in his stories easily identify with inanimate objects. That makes it effortless to claim that he is the one to put emphasis on nonhuman characters more than any other Iranian contemporary fiction writer. Not being classified as a political writer, he occasionally depicts desperate characters on the verge of giving up their hopes, in order to reflect the challenging political conditions of the society.

The most prominent characteristic of Najdi’s fiction is the poetic language and the bold lyricism in his narrative style. He is perhaps the most successful Iranian contemporary fiction writer to have amalgamated poetry and fiction in an artistic yet plebeian manner. It’s fair to claim that his stories are lengthy lyrics in prose. Despite the fact that his experimental style has brought about a lot of controversies among the literary critics, he has successfully opened a new window to the world of fiction by his poetic style like no other Iranian contemporary novelist has done.

Not quite a political writer, he tackled many issues in Iranian contemporary history and politics such as the Iran-Iraq War, the rise of communism in Iran, the issue of political prisoners, the Jungle Movement of Gilan[1] and the Siahkal incident[2]. Despite the fact that a few of his stories are particularly about war and other notable historical events, he tends to build up his fiction around trivial issues without necessarily being followed by an incident. His narrators are often very humane in their attitude and his tone is very humble and intimate. He identifies with the most vulnerable cast of characters, ranging from a racing horse that is doomed to draw a cart to the point that the cart becomes a part of its flesh, to an old couple with no children who hire a dead infant to bury him as their own child.

In his endeavor to write experimental stories with versatile themes, motifs, and settings, he usually builds his stories around a supernatural incident which is followed by the reactions of his realistic characters as if tackling an ordinary issue. This is the dominant characteristic of his fiction for which it can be classified as magic realism. For example, in his story “A Native American in Astara”, he artistically portrays a displaced Native American character with a magical fluid that he offers to two Iranian townsfolk as a souvenir, leading them to reveal a local truth through the foreign magical reality that the Native American personage offers. The story is portrayed through fragmented flashbacks to the life of a Native American tribe as a story within a story. The Native American extra layer enables Najdi to echo the supposedly forbidden issue of the massacre of Kurds in a language that is thick with symbols and metaphors.

Najdi had been living far from the literary circles in the capital Tehran for the most part of his life. However, his rich prose and the array of techniques he employs to compose his stories make him the subject of many academic studies in his homeland. His renowned story collection, The Leopards Who Have Run with Me, is perhaps among the most debated and reviewed works of fiction in the last decades in the Iranian literary scene.

[1] A local rebellion against the monarchist rule of the Qajar central government of Iran from 1914 to 1921. [2] A guerrilla operation against Pahlavi government organized by Iranian People’s Fadaee Guerrillas that happened near Siahkal town in Gilan on February 8, 1971.

BIBLIO BRIEF

- The Leopards Who Have Run with Me (1994)

- Down the Same Streets Again (Markaz: 2000)

- Unfinished Stories (Markaz: 2001)

- The Sisters of this Summer (Mahriz: 2002)

- Reality is My Dream (Markaz: 2013)

Leave a Reply