Paul Auster once called translators “the shadow heroes of literature, the often forgotten instruments that make it possible for different cultures to talk to one another.” Parsagon’s new year resolution is to introduce the most prolific and internationally-acclaimed Iranian translators in appreciation of their contributions to cultural approximation.

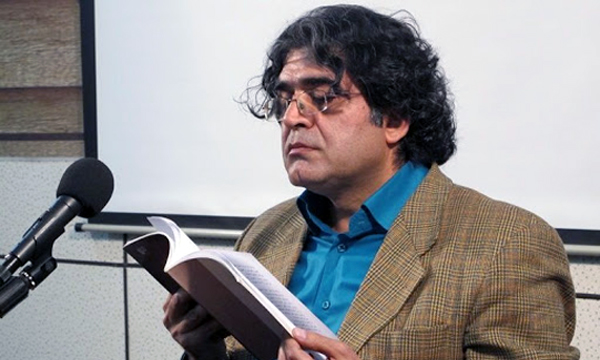

Ali Abdollahi was born in Khorasan, Iran, in 1968. He studied German language and literature at Shahid Beheshti University in Tehran, and specialized in Concrete Poetry. Between 1993 and 2001 he worked at Radio Iran, bringing both German and Persian literature to its listeners. Abdollahi has also worked as a university professor, journalist and translator. He has published more than twenty translations, including works by Rilke, Nietzsche, schopenhauer, and Hermann Hesse. Abdollahi is also a poet with international achievements. Two of his published volumes of poetry are translated into German: Immerfort gehe ich im Dunkeln (1997) and So kommt sie nicht mehr (2003).

PARSAGON: Which works of world literature would you mark as the most influential on your life and career? How have they moved you?

ABDOLLAHI:

An author is usually influenced by all the books he reads, and it is difficult to choose the exact titles. Moreover, I had a special childhood with unique lessons and a life spent with agricultural and pastoral duties. I was born into an illiterate farmer and a sheep-owning family in a village in southern Khorasan where I lived until I was eighteen. Our village had no electricity before I turned sixteen. Of course, that family background and that kind of life and childhood also affected the type of studies I received. First, I was almost always the top student, but since there was no library in the village, I had no books available for me to read; and since I was the first-born child, I had no one in the family to tell me what to read. And because we did not have a television, my childhood was completely devoid of the collective visual memories of middle-class and lower-middle-class children. That is, I had no idea of the cartoons and other children’s movies or sports. Everything I read was either found by chance, or the result of trial and error, the advice of high school teachers, and personal curiosity. At that time, only oral literature and folklore songs and tales entertained me and fueled my imagination. After the third grade, I moved to town to attend high school. And there I happened to be the pupil of two poet-teachers – quite literate teachers indeed! I have been reciting poetry since the second year of high school, and under their guidance and supervision, I had read the entire works of ancient Iranian poets by them time I finished high school. Later on, again by chance, I became acquainted with an old and rare Persian translation of Thus Spoke Zarathustra, and that was how I began to read other works of Western literature and modern poetry. Some of the most important and influential works on the formation of my thought in those years are more or less as follows:

1. Rumi’s lyric poems

2. ‘Haft Peykar’ or The Seven Domes of Nezami Ganjavi

3. Attar’s heroic couplets, or ‘Masnavi’

4. Khayyam’s quatrains

5. Thus Spoke Zarathustra by Nietzsche (translated by Nayer Nouri)

6. Faust and Goethe’s East-West Divan (translated by Hassan Shahbaz and Shafa)

7. The Persian Samak-e Ayyar* [سمک عیار] and Don Quixote by Cervantes.

In the last years of high school, while reading Thus Spoke Zarathustra, I had a revelation: I had come across a strange philosopher many of whose lines I could not understand, yet I had a feeling that of his words by essence made sense to me; this book had a great impact on me. A while later I read Goethe’s Faust and West-Eastern Divan, each with different effects. I still do not forget the strange and complex character of Faust, who somehow represents modern man in all its dimensions. Goethe’s Eastern Divan also reveals the dialogue between two geniuses in two different times and places, and although it is not a brilliant work in terms of poetry and imagination, the very act of writing such a book shows how ideas travel from one culture to another. The scope and permanence of these influences were so robust that I later became a translator of Nietzsche and Goethe and other great figures of German literature and philosophy. I was likewise fortune to get the first, black-covered, volume of Samak-e Ayyar edited by Parviz Khanlari, and as I finished reading it, I was astounded by the similarity of its stories to the very oral tales that the illiterate rural elders used to tell each other, with slight nuances, on winter nights. There I came to realize how literature has spread and survived over centuries in the most illiterate societies. And of course Don Quixote, this universal and memorable character who never gets old: comparing these two books of romance with some contemporary Don Quixotes living around me suffices to make this book everlasting in my mind.

PARSAGON: In your opinion, which literary/artistic texts from Iran should the world read or see? Please mention your top seven choices and why you have chosen them.

ABDOLLAHI:

Almost no good work of contemporary literature and no author has been properly translated into other languages. Accordingly, the long list of suggestions may pile up to the skies. I also have a lengthy list of personal suggestions that might not fit this limited space. Below are just a few works and collections that I remember and would have loved to translate or recommend to the world had I ever had the opportunity:

1. Re-translation of the Persian classics: The translation of ancient Iranian literature, especially its mystical heritage, has been attempted for almost five centuries, but the translations are not all good. And more importantly, almost all but Khayyam, Hafez and Rumi have been neglected. Introducing them with a modern perspective and a new language can show the importance and greatness of these ideas in a period dominated by strict Islamic Salafism – and would make a change. On the other hand, the significance of the Iranian poets’ efforts to remove the sharp sword from and maintain equilibrium within radical Islam is yet unknown to the world.

2. Complete poems of Shamlou: to introduce the wide spectrum of this activist and persistent poet’s creativity, as well as to get acquainted with the state of social developments in the context of contemporary Persian poetry.

3. Mohammad Ghasemzadeh’s novels, due to the diversity of local narratives and experiences and various elements of Iranian culture.

4. The Infernal Days of Mr. Ayaz by Reza Braheni: in order to get acquainted with creativity in modern Iranian literature and the history of censorship, restriction and elimination.

5. Bijan Jalali’s poems, due to the poet’s deep thought, which – in sharp contrast to Shamlou – has been expressed in the simplest possible language not benefiting from any literary devices or metaphors.

6. The novels of contemporary women writers are certainly numerous, but they are a new and growing trend and need to be translated and recognized by the world.

7. The novel Dark Moon by Mansour Alimoradi, because of the introduction of the typical geography of the western regions of Baluchistan, the southern and eastern Kerman, and their inhabitants along with all their special and strange stories as well as new perspectives and fascinating narratives.

PARSAGON:And finally,What do you think literature can do (or should do) in times of global crises, such as the pandemics?

Literature is constantly created under impasse: economic hardships, political repression, loneliness, individual and collective sorrows, and periods of great and crushing failures. Therefore, in my opinion, literature has always survived in any circumstances and mirrored the conditions, pressures, and aspirations for improvement and aperture. Today literature relies less on individuals, single and large giants, and more on collective movements, and becomes influential in its continuous and consistent process. Its impact is no longer that of causing revolutions as it used to do before, rather slowly yet persistently altering the tastes and thoughts of people.

During the pandemic, the personal experiences of poets and writers do not differ much from before: they have always written and are still writing in solitude and isolation. Yet this time, the audience is also drawn to isolation and distancing, and this is quite a change that has not previously been experienced. This may lead to more empathy between the writer and the reader. Perhaps the consumers of literature will have the opportunity to think like the authors, and together they might find a solution for saving the earth from environmental crises, air pollution, and even mental pollution caused by redundant relationships they used to find unavoidable before. Now they can see that many of these mental and behavioral disorders and destructive acts can be avoided. Literature will certainly be different after such a universal human experience on the planet. The difference will, of course, be partially positive and partially negative.

PARSAGON: Thanks a lot for your response.

* Dr Behzad Ghaderi, who has also recommended the translation of this work, translates the title to Samak the Con-Man.

Leave a Reply