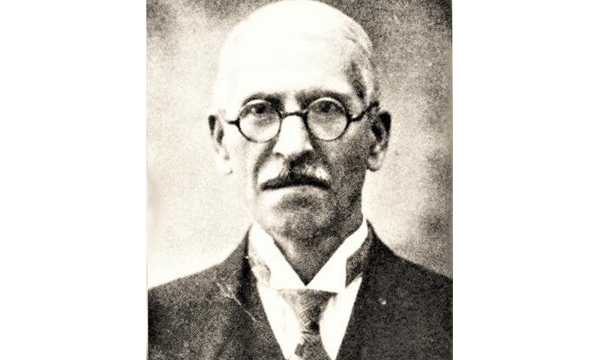

Qazvini, Mohammad (Tehran, 30th March 1877 – 27th May 1949) [10th Farvardin 1256 – 6th Khordad 1328]. A pioneer in the field of literary and historical research in modern Iran, one of the early experts in textual criticism and bibliography, and a reputable and celebrated scholar in the field of Hafez Studies. He was the eldest child of a family well-known in both the social and scholarly worlds. His grandfather, Haj Abdal-‘Ali Golizuri, was the headman of Golizur village near Qazvin, and his father, Abd-al-Wahhab bin Abdal-‘Ali Qazvini – also known as Abd-al-Wahhab Golizuri Qazvini – was more widely known as “Mulla Aqa”, one of the authors of the Nama-ye Daneshvaran encyclopedia (one of the reference works of the era of Naser al-Din Shah Qajar), and was also a teacher at the Mo’ayer al-Mamalek school of Tehran.

Mohammad Qazvini – also sometimes pen-named as Qazvini al-Golizuri, in reference to his ancestral homeland – was born in the Darvazeh District of Tehran. He studied subjects that were typical of his time – Arabic literature, grammar and syntax, and the principles of foreign jurisprudence, wisdom and speech – with his father, and then with the great masters of the period (Hajj Sayyid Mostafa Qanat Abadi, Sheikh Mohammed Sadeq Tehrani, Sheikh Fazlollah Nouri, Hajji Sheikh Ali Nouri, Mullah Mohammed Ali Amali, Hajji Mirza Hassan Ashtiyani, Sheikh Hadi Najm Abadi, Sheikh Mohammed Mehdi Qazvini Abd-al-Rab Abadi, Aqa Sayyid Ahmad Adib Peshawari, Mohammed Hossein Foroughi) at the schools of Mo’ayer al-Mamalek, Marvi and Khazen al-Molk. During the same period, he studied French to an advanced level with Mohammad-Ali Foroughi at the Alliance school of Tehran. It was during this period that his intellectual interests and his inclination for new, previously under-investigated topics of research took shape.

It seems that Qazvini’s constant communication with Mohammad-Ali Foroughi during that period, along with his boundless enthusiasm for viewing rare original manuscripts and the encouragement of his brother (Mirza Ahmad Khan, who was living in London at the time) had played no small role in fostering his desire to travel to Europe. On the 19th of June, 1904 [29th Khordad, 1322], he traveled to London via Russia, Germany, and the Netherlands. Qazvini’s stay in the West stretched to 35 years, which he spent engaged in extensive historical, literary and cultural research in London, Paris and Berlin. He became acquainted with a number of great Orientalists, including Anthony Ashley (1859-1933), George Ellis (1851-1942), Henry Frederick Amedroz (1854-1917), Edward Brown (1862-1926), Hartwig Derenbourg (1844-1908), Clement Huart (1854-1926) and Eduard Sachau (1845-1930), with whom he engaged in academic communication, providing them with a great deal of help in their research on Iran and Islam. He accepted an invitation from the trustees of the Gibb Memorial Trust to produce a critical edition of the Tarikh-i Jahangushay, and took pains to join the circle of great Iranians living in Europe at that time (including Dehkhoda, Hajj Sayyid Nasrallah Taqavi, Ebrahim Pourdavoud, Mohammad-Ali Jamalzadeh, Sayyid Hassan Taqizadeh and Hossein Kazemzadeh Iranshahr). He attended the weekly meetings of the Literary and Scientific Association of Taqizadeh’s Kaveh magazine, and collaborated with him on its publication. He visited renowned academic libraries and the treasure troves of manuscripts in the museums of Paris in order to continue his research and editing work, and finally began to reap the rewards of his academic pursuits. Staying in Europe was an opportunity for Qazvini to develop a truer synthesis between traditional Eastern research methods and new Western approaches, and allowed him to lay more tangible examples and advice at the feet of those Iranian researchers who came after him. Naturally, he explicitly acknowledged that part of his own success in the world of research during the period that he lived in Europe was the moral and material support of people like Edward Brown, Hossein-Qoli Khan Navvab (the acting Iranian Ambassador in Berlin), Sayyid Hassan Taqizadeh, Mohammad Ali Foroughi, Nasir al-Dawla Firouz Mirza (the acting Minister of Foreign Affairs), and Mirza Hassan Khan Vosough al-Dawla (the acting Prime Minister).

When the beginning of the Second World War in the late summer of 1939 coincided with a worsening of Qazvini’s living conditions in Europe, he emigrated from Paris to Istanbul, and after a short stay returned to Tehran via Khanaqin in Iraq, Kermanshah, Hamedan, and Qazvin, finally settling in Hesar Bouali village in the Shemiran district. During this period, Qazvini’s house played host to a number of mutually beneficial gatherings for luminaries of the history, culture and literature of Iran.

In the fall of 1948, Qazvini’s fortunes turned, and after a period of illness, he passed away. His body was buried next to the tomb of Sheikh Abu al-Futuh al-Razi (in the Shah Abdol-Azim Shrine in Rey).

As an academic and cultural figure, Qazvini has always been accorded a great deal of respect and praise by scholars of contemporary Iranian history, and the degree of admiration that he commanded was finally made manifest in his title of allamah. A critical approach to the research and writings of Orientalists and Western Iranologists, and the ability to study their work without engaging in cultural and intellectual self-erasure were Qazvini’s hallmarks, and so too was his deftness in critically editing literary and historical texts, along with the sensitivity and quick temper that formed the essence of his character. He was insatiable in his reading and in seeking out knowledge and understanding both in academia and in the world around him, avoided making hasty judgements in his comments and observations, and was scrupulous to the point of obsession in academic discussions. It is by virtue of these attributes that Qazvini has continuously occupied such an unparalleled position in the hearts and minds of his contemporaries and the scholars who came after him.

Qazvini’s work on Hafez represents the pinnacle of his writing and research; so much so that in the history and culture of Iran, the names of the two are inextricably linked. To Qazvini, the most sublime position in art, poetic method and thought belonged to Hafez of Shiraz; when acknowledging this preoccupation, Qazvini mentioned that throughout his life, once every six months he carefully read the Divan of Hafez through from beginning to end. “I owe it to myself to take an appreciation of the poetry of Hafez of Shiraz to be one of the key measures of common sense and good taste. Every Iranian that I meet for the first time, if they are to a degree a person of grace and manners – that is, if they are not completely common – that is, if they’re not some straight-talking mathmetician or spiritless mechanic or a doctor engaged in simple material research – I judge their good taste (or lack thereof) by their devotion to Hafez (or lack thereof). If I see that they are not fascinated by Hafez, then no matter how much I kill myself over it, there won’t be the slightest compatibility between us. And if, God forbid, I see that they condemn Hafez, then I consider them an ass in the slaughterhouse of man, and pass them by.” In addition to this, Qazvini’s critical edition of the Divan of Hafez, produced with the help and collaboration of Qasem Ghani, was received with such adulation that after its publication, the name “Qazvini” came to be considered an adjective that could be attached to the name “Hafez”, and the expression “Hafez Qazvini” became common.

Biblio Brief

Hafez Studies

- Divan-e Khwaja Shams al-Din Muhammad Hafez-e Shirazi, by Mohammad Qazvini and Dr. Qasem Ghani, with a 93-page critical introduction by Mohammad Qazvini. Tehran, Ministry of Culture, 1941 [1320]

- Several introductions to Hafez research and the works of Hafez, including: a critical introduction to the Divan of Hafez; an introduction to the lyrics of Hafez; a comprehensive introduction to the Divan of Hafez, with critical annotations; and an introduction to the history of the age of Hafez.

- Articles about Hafez: Hafez wa Soltan Ahmad-e Jalayir (‘Hafez and Sultan Ahmad Jalayir’); Mir-e-Nowruzi; Shahed-e Digar Baraye Mir-e-Nowruzi (‘Another Testament to Mir-e-Nowruzi‘); detailed interpretation of one of Hafez’s verses; Bad Shurteh (‘Wind Conditions’); Melek-e Suleiman (‘The Kingdom of Solomon’); Emad al-Din Mahmoud Kermani; Moluk-e Hormoz (‘The Kingdom of Hormoz’); Bazi Tazminha-ye Hafez (Tazmin az Asha’our-e Arabi) (‘Some Quotations in Hafez: Quotations from Arabic Poetry’); Some quotations by Hafez (from Arabic poetry); Bazi Tazminha-ye Hafez (Tazmin az Asha’our-e Farsi) (‘Some Quotations in Hafez: Quotations from Persian Poetry’); Divan-e Hafez be Ehtemam-e Khalkhali (‘The Divan of Hafez, by Khalkhali’).

- Ten letters about Hafez to Dr. Qasem Ghani

A collection of Qazvini’s works on Hafez has been published under the title Hafez az Didgah-e Allamah Mohammad Qazvini (‘Hafez from the perspective of allamah Mohammad Qazvini’), by Ismail Saremi.

Other selected works:

- Tarikh-i Jahangushay, by Ala’ al-Din Ata-Malek bin Baha’ al-Din bin Mohammad Jovayni, edited by Mohammad Qazvini. Brill Publishing, Leiden, Holland. 1911 [1329].

- Bist Maqala-ye Qazvini (‘Twenty articles by Qazvini’), ed. Ebrhaim Pourdavoud, Iranian Zoroastrian Association, Mumbai. 1928 [1307].

- Bist Maqala (second volume), ed. Abbas Iqbal Ashtiani. Tehran, 1934 [1313].

- Marzban-nama, critical edition with annotations by Mohammad Qazvini. Brill Publishing, Leiden, Holland. 1947 [1326].

Sources:

Shahr-e Hal-e Injaneb Abd-al-Wahhab Qazvini (autobiography), Tarikh-i Jahangushay by Ala’ al-Din Ata-Malek bin Baha’ al-Din bin Mohammad Jovayni, ed. Mohammad Abd-al-Wahhab Qazvini, Brill Publishing, Leiden, Holland, 1911 [1329]; Zendeginama Khod Nevesht-e Ustad (autobiography), Mohammad Qazvini, Hafez az Didgah-e Allamah Mohammad Qazvini, (‘Hafez from the perspective of allamah Mohammad Qazvini’), by Ismail Saremi, Elmi Publications, Tehran, 1988 [1367], pp. 22-43; Yadi Digar az Qazvini (‘Another memory of Qazvini’), Ebrahim Pourdavoud, ibid., pp. 45-52; Allamah Mohammad Qazvini, Mojtaba Minavi, ibid., pp. 53-60; Allamah Mo’aser (‘The Contemporary allamah‘), Dr. Mohammad Moin, ibid. pp. 89-122; Wafiyat-e Mo’aserin: Allamah Mohammad Qazvini (‘Death of Contemporaries: allamah Mohammad Qazvini’), Abbas Iqbal, Nama-i Farhangistan, May 1950 [Khordad 1329], p. 27; Zendegi Tufani: Khaterat Sayyid Hassan Taqizadeh (‘Stormy Life: The Memoirs of Sayyid Hassan Taqizadeh’), by Iraj Afshar, Elmi Publications, Tehran, 1993 [1372], pp. 185, 344, 351; Yaddashtha-ye Ruzane az Mohammad Ali Foroughi (‘The Diaries of Mohammad Ali Foroughi’) by Iraj Afshar, Library, Museum and Documentation Center of the Islamic Consultative Assembly, 2009 [1388]; Yaddashtha-ye Doktor-e Qassem Ghani (‘Memoirs of Dr. Qassem Ghani’) by Dr. Cyrus Ghani, Tehran, Zevar Publications, 1998 [1377], vol. 3 pp. 548-574; Allamah Qazvini wa Shiva-ye Gharbi-ye Tahqiq (‘Allamah Qazvini and the Western Method of Research’), Mahmoud Omidsalar, appendix 33, Ayene-ye Miras journal, 2014 [1393].

Leave a Reply